Quoting, sampling, remixing existing music is commonplace in various popular genres but, generally, not nearly as commonplace in orchestral, choral or chamber music. There are of course exceptions, as with most things, but in general this practice is absent in and around various forms of art music.

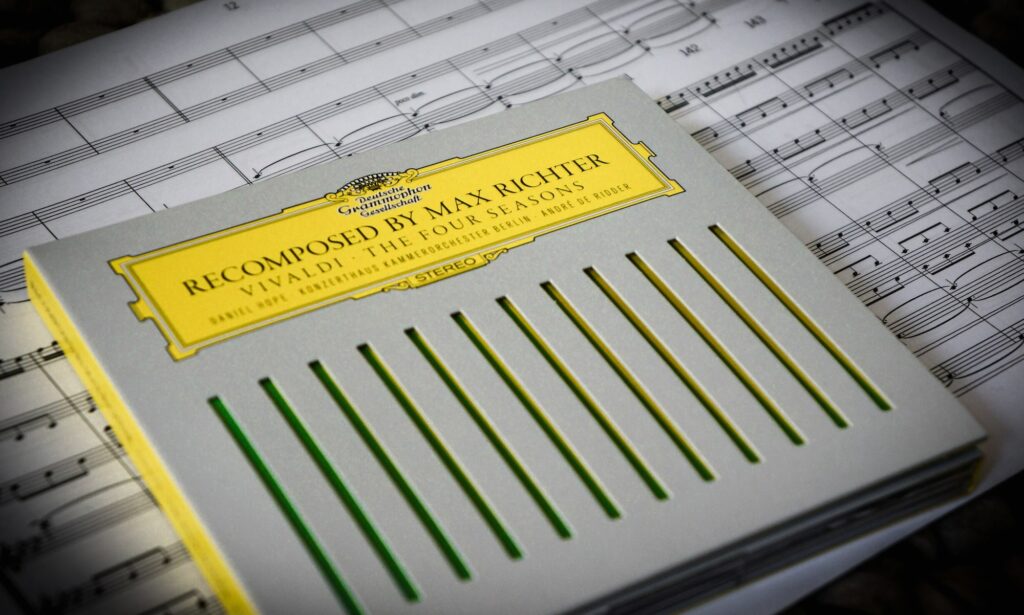

One fairly recent exception is German-British composer and pianist Max Richter‘s “Recomposition” of Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons (a work that incidentally I also discussed in an earlier blog post). Ivan Hewett described Richter’s take on Vivaldi as a work “which suggests that after years of tedious disco and trance versions of Mozart, the field of the classical remix has finally become interesting” in his review.

Max Richter has, at his own estimate, taken about one quarter of Vivaldi’s original material from the four concertos. This material has been reconstructed, looped, phased and treated in other ways to create this new musical work that sounds both modern in a minimalist (or even post-minimalist) way and, at the same time, classical.

Ivan Hewett again describes in The Telegraph Max Richter as consiously exploring and exploiting the clashes between the patterns in Vivaldi’s musical style and those in his own, writing that “the friction between them generates a fascinatingly ambiguous colour”.

It is quite interesting to listen to Richter’s take on Vivaldi, knowing the original music quite well, as Richter constantly plays with your expectations. Some phrases appear nearly verbatim except for perhaps one beat being omitted, thrusting the music forward.

Other times, Richter’s minimalist background shines through even more clearly when he takes short passages from Vivaldi and repeats them in the style of American minimalist composers like John Adams.

Harmonically, Richter adds sustained notes or new bass notes to chords that appear otherwise unchanged, again adding dashes of contemporary seasoning, if you would, to Vivaldi’s music. Other parts are bathed in a generous reverb, bringing an almost surreal, otherworldly dimension to the music.

Depending on your own personal taste and disposition, you may be thinking: Why bother? Why “destroy good music” (as a friend of mine described this practice)? Well, if you ask me, this is far from destroying music. The original work is still available to us, and thanks to diligent research by ensembles such as La Serenissima we know much about how to perform it as they might have in Vivaldi’s own time. (Again, go read my previous post if you haven’t already, for more information about the original Le Quattro Stagioni!)

Also, I think that this kind of practice, if done well, allows us to reappraise and rediscover older music. And I do personally think Richter’s work here is an example of this. Richter offers a new perspective on several hundred years old music that has, in some respects, been played to death and back. Vivaldi’s “Seasons” are a kind of musical meme in itself, as is the perception of it as worn out, clichéd music.

An even more recent example is English composer Anna Clyne and her dramatic, evocative chamber orchestra piece “Sound and Fury“, composed as recently as 2019. In her programme notes, Clyne writes that she wants “to take the listener on a journey that is both invigorating – with ferocious string gestures that are flung around the orchestra with skittish outbursts – and serene and reflective – with haunting melodies that emerge and recede”.

And what a journey it is.

The piece erupts immediately with outbursts that are more violent than skittish and, as a whole, it does lean more toward ferocity, rather than serenity. In Anna Clyne’s case, her raw material comes from Joseph Haydn‘s 60th symphony, nicknamed “Il Distratto” because it makes use of incidental music Haydn wrote for a theatre production of a play with the same name.

Anna Clyne listened to the Haydn symphony several times from beginning to end, writing down which parts of the music caught her ear. Just as Haydn’s symphony is in six movements (which is exceptionally odd for a symphony written in the 1770s), Clyne’s work is made up of six parts, “following the same musical trajectory” as Clyne herself explains it, as Haydn’s music.

The title of the piece comes from Macbeth‘s last soliloquy, delivered upon learning of his wife’s death, which ends thus: “It is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” The complete soliloquy is incorporated into the work, either played back from a taped recording or recited live in concert by a narrator.

It is often much harder to recognize Haydn in “Sound and Fury”, apart from the more obvious cues, than in Max Richter’s work. However, both composers have had different starting ideas: While Richter set out to make essentially an arrangement of Vivaldi’s original work, Clyne’s composition is an entirely original piece that uses material from older music as building blocks.

Nevertheless, it is a fascinating detective job to listen to Clyne and Haydn back to back and identify all the cues she has borrowed. I did this with my composition students at the folk high school in Härnösand last week, also discussing the inherent limitations and possibilities of this type of composition process and what it might mean for the music itself.

Finally, I tasked my students with writing a short piece of their own using this method. They had from Monday afternoon to Thursday evening to finish, so I only expected a 1–2 minute piece for a smallish ensemble. For our building blocks, I chose Maurice Ravel‘s suite “Ma mère l’Oye“, specifically the fourth movement: “Conversation of Beauty and the Beast”. (Why not listen to this lovely recording with the New York Philharmonic and Leonard Bernstein?)

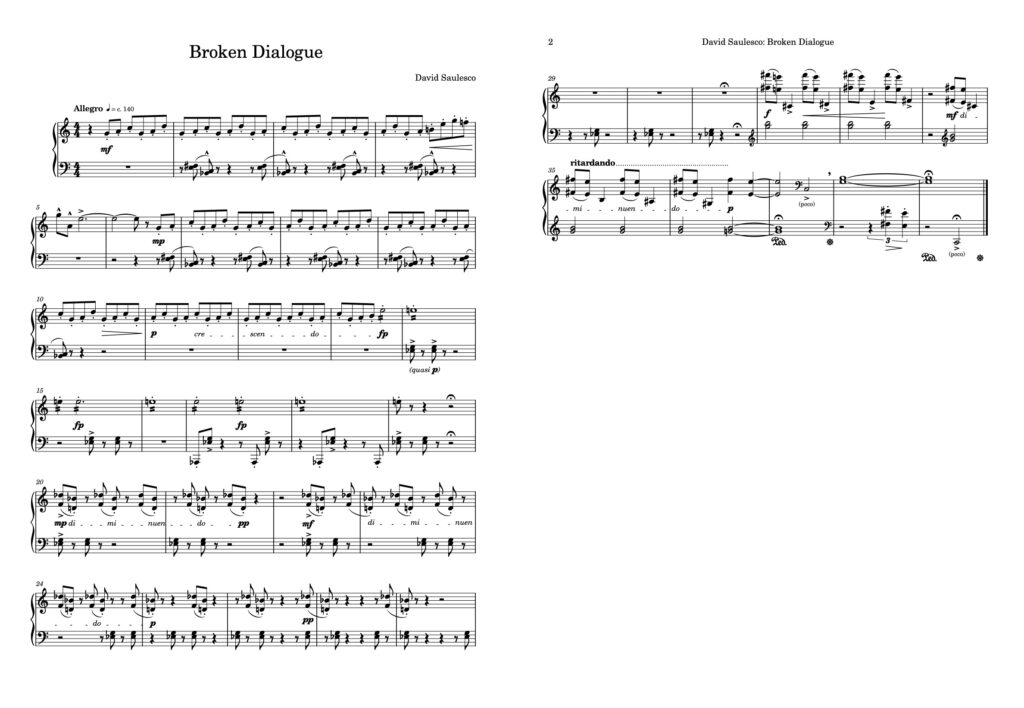

Not wanting my students to have all the fun, I decided to put my money where my mouth is and try to write a short piece like this of my own. I gave myself one afternoon to work on it, and while I can safely say that it is far from my best work, it did end up a cute little ditty that I think has a distinct Saulesco sound, even though the notes themselves are basically cut and pasted from Ravel. What do you think?