Another week, another composition sent off to the musicians. Not an entirely new work this time, but still!

Since I was a teenager, I’ve wanted to be able to play the bassoon. It’s one of those instruments that aren’t as obvious as violin, guitar, drums, piano, or even flute, bass guitar, cello or trumpet. I at least have a feeling that the bassoon is one of those instruments that are usually overlooked. While I can’t be entirely sure anymore, my oldest distinct memory of falling completely in love with the basson is of discovering the English progressive rock band Gryphon.

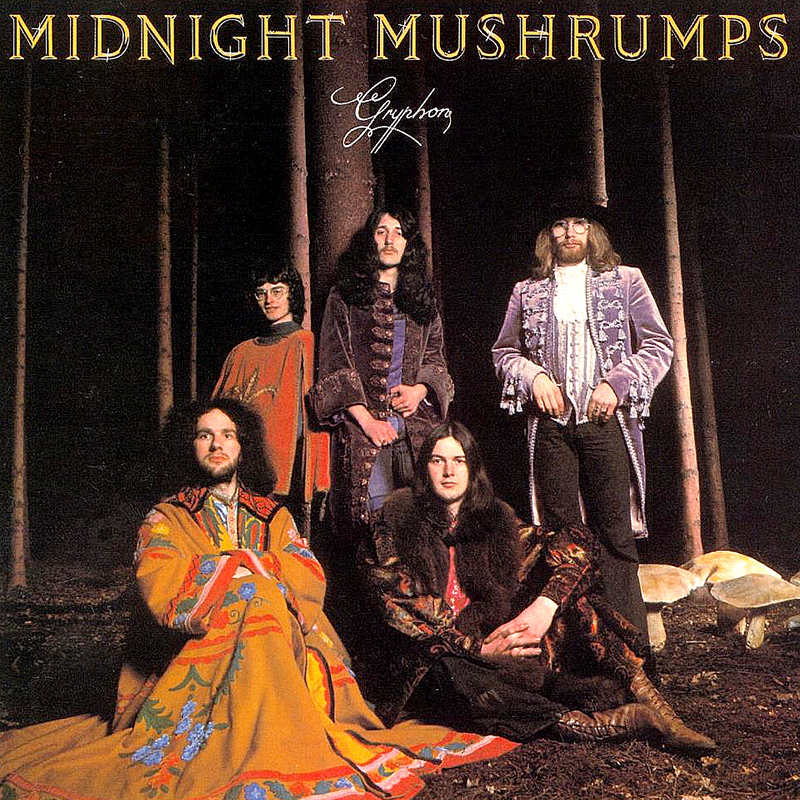

Isn’t this cover art simply amazing? It’s so evocative and intriguing and simultaneously strange and confusing. This particular album is the group’s second outing, released in 1974. Side one contains the 19 minutes long title track, a portable-sized prog epic that takes you on quite a journey. And what instrument takes the lead right from the off? Well, the bassoon of course, high up in its beautiful tenor range.

Gryphon released five albums between 1973 and 1977, ending with the aptly named “Treason” that supplanted the group’s signature sound with a much more mainstream-leaning pop material flavoured with Gryphon stylings.

However, that was, as they say, then and this is now. And now Gryphon lives again. Self-proclaimed as “the oldest and the newest thing”, the band reunited for a one-off live concert in 2009, then played a few more gigs in 2015 and finally released their first album in 41 years in 2018, followed by yet another in November of last year. And mad genious/multi-instrumentalist Brian Gulland still plays a wicked bassoon.

That turned into quite the tangent. I really do want to impress upon you, though, that learning how to play the bassoon has been a dream of mine for a while now, and while that dream may not come true, at least I have had the opportunity to write music for a pair of brilliant musicians, one of which is a bloody brilliant bassoonist. The other might not be a bassoonist, but he is in fact a rather brilliant pianist and organist.

I believe it was in December 2019 that my friend Olof called me, ecstatic, to tell me two things: One, he had recently heard Sebastian Stevensson give a smashing performance of the solo concerto Baboon Concerto (written for him, no less, by composer Fredrik Högberg) with the DR Symphony Orchestra, and two, he had engaged Sebastian to perform at Olof’s annual summer concerts the following year. This meant that Olof needed music for Sebastian to play and so he asked me to write something. Henrik had also been engaged at that time, so I settled for bassoon and piano.

My immediate idea, after deciding on those instruments, was actually to write a sonata. I liked the thought of taking an established, well-known musical structure and filling it with new and hopefully (!) unexpected musical content. The three-movement format I chose was familiar to 18th century composers like Haydn and Mozart, with two fast movements flanking a slow one, but the musical content of these movements have more in common with the 21st century.

The first movement of my Sonata for Bassoon and Piano is called Chaos Theory. (Yes, named after that chaos theory.) In another nod to classical sonatas, the first movement is composed in sonata form. However, while I follow the overall structure of the sonata form, I do play a little fast and loose with its rules.

A sonata form piece’s first part, the exposition, typically introduces two sets of themes, two subject groups. These are presented, and later developed, in specific keys based on in which key you began. (It’s more complicated than this, but I’ll leave it to you to find out more.) My first theme is based on a twelve-tone row, which more or less makes the whole idea of key relationships moot. At least my second theme is a (fairly typical) fugue.

The second movement, Daydream, starts out as little more than vapour with arpeggiated, richly coloured piano chords that might bring French Impressionists to mind. (But not Debussy, because he was not an impressionist.) The dream gradually gains shape and momentum, but it is a restless dream and not a happy one, and it comes to a dramatic climax before it fades back away into obscurity.

The third movement started out with the name: Sinkadus. I decided on the name before I had any idea how to connect it to the music. The term originates in two Old French words, “cinque” and “dous”, which mean “five” and “two” respectively. It is commonly known as a gambling term, referring to a dice throw resulting in a five and a two. I came across the term in Finna dolda ting, an absolutely delightful book recounting Swedish tabletop role-playing game culture in the 20th century. “Sinkadus” was a popular tabletop gaming magazine founded in 1983.

I ended up interpreting the five and two idea literally. The better part of the third movement is written in alternating two- and five-note metre with a generous helping of rhythmic variation to avoid monotony. Also, the main musical material of the theme is based on a cadential chord progression known as the two-five-one turnaround. I stacked a series of such cadences one after another in a sequence until the music had gone all the way around the circle of fifths. Lots of twos and fives, in other words.

Seemingly disparate parts, in other words, that still make up a pretty neat package – at least in my opinion. And it is definitely not dull. Not to mention that both Henrik and Sebastian have plenty to do – if anything, they definitely do not have many dull moments.