I am truly blessed to come across such a wealth of wonderful and amazing people in my life. From musician colleagues to dear friends and acquaintances, close as well as extended family members, as well as helpful and pleasant hotel and train staff and unexpected acquaintances made along the way.

To be frank, I am still overflowing a little with emotion after last night’s concert. It was a wonderful experience and it went swimmingly. An enthralled audience of seventy-odd listeners seemed to really appreciate our mix of Swedish contemporary music with French compositions from the early 20th century. I was a little nervous opening the concert myself with my two art songs, Klangen and Trädet och skyn – the first being a world premiere, at that – but I felt so comfortable performing with the wonderful pianist Henrik that my nerves quickly settled.

I really want to stress the importance of connecting with your fellow musician or musicians, and the many levels of connection you can make. It is possible to feel quite content with one musician or group of musicians, not having any particular complaint or remark, but with some musicians you just “click”, as they say. I felt like Henrik and I made that kind of connection several times last night during our performance, short as it was.

Henrik and Sebastian also performed a sonata for bassoon and piano by French composer Charles Koechlin, chosen by us in part for it being a great aesthetic fit to my own sonata. In addition, Henrik alone performed four of six piano pieces commissioned in the early 20th century to mark the centenary of Joseph Haydn’s death. The arguably most famous composition, Menuet sur le nom de Haydn by Maurice Ravel, was also my personal favourite, although Reynaldo Hahn’s Thème varié sur le nom de Haydn was also very sweet and enjoyable.

Common to all the Haydn pieces was that they were based on, or featured prominently, a five-note theme constructed from the surname “Haydn”. Three of the letters correspond directly to tones in the Western scale system (H being the German name for B for historical reasons); the remaining two – Y and N – were assigned tones by counting letters in the Western alphabet:

A coincidental connection between the Haydn pieces and my Sonata for Bassoon and Piano is that I also included a similarly constructed musical theme. Being the egomaniac that anyone who knows me can attest to that I am, that theme is constructed from my own name.

”But maestro,” you might be asking (see? Total egomaniac), ”there is no V, I, S, U, L or O tone. How could you possibly construct a melody out of those letters? Surely not even someone with your near-limitless musical capacity could accomplish something so seemingly impossible?”

I’m glad you asked, young padawan.

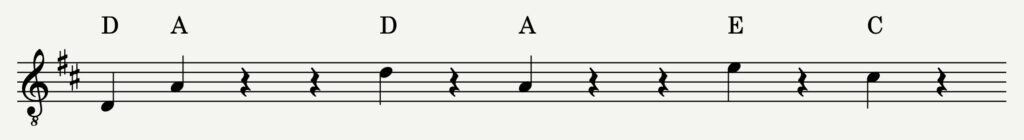

To begin with, four letters have obvious corresponding tones: D, A, E and C. But this only gets us so far:

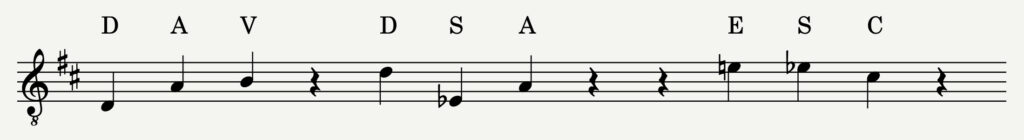

However, with a little linguistic legerdemain, S also can be said to have a corresponding tone: E-flat, specifically by its German name, “Es”. Furthermore, what is the letter “V” but a soft “B”? In this case, I specifically chose the tone B, which is the same as the German H. This gives us the following:

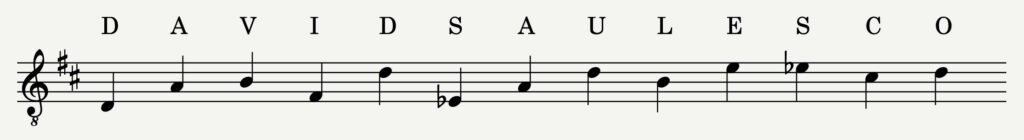

For the last four letters we turn to solmisation for a number of increasingly less obvious (and perhaps more tenuous) connections to tone names. I wanted to construct a complete theme incorporating every letter in my full name and found the solmisation system’s syllables very useful for this. The letters I, L and O pair reasonably well with the syllables “mi”, “la” and “do” respectively. U, on the other hand, is trickier.

The Western solmisation system has often been attributed to one Guido of Arezzo, a Benedictine monk and music theorist living around the turn of the first millennium. In its earliest form, the first step on the scale was actually called “ut”! Only some six hundred years later, Italian musicologist Giovanni Battista Doni renamed it “do” (and added the seventh step, which he named “si”).

“Ut” is still in use in the French-speaking world. (And, on a side note, the English music educator Sarah Anna Glover renamed “si” as “ti” in the 19th century so that every syllable would begin with a different letter.) In solfège, which is a music education method based on solmisation, these syllables can either represent specific notes in the diatonic scale or different scale degrees, irrespective of key. Considering that this anagrammic melody I am constructing is in the key of D major, we end up with this series of notes:

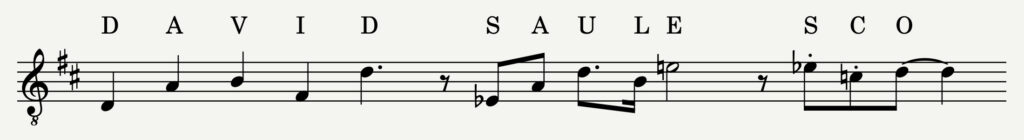

And finally, with a dash of rhythmic zest, I came up with this melody which I use as a fugue theme in the first movement of my Sonata for Bassoon and Piano:

The first entry of this melody is in a three-voice fugue, early on in the movement. Towards the end it comes back in full force, this time in a four-voice fugue. Shades of this melody also appear in the work’s two latter movements, but it is only used prominently like this in the first.

Tomorrow, I fly to Spain with the wonderful members of Ensemble Villancico. We have had some quite warm and sunny days over here in the past weeks, but nothing even close to the daytime temperatures of 36°C that await us down there. Even my summer-loving fiancée admitted that was a little too much. In fact, the global prevalence of such temperatures, and their effect on the world, are no laughing matter.

At the very least I know one furry friend of mine who is well happy that she didn’t have to come along for this trip and suffer those temperatures with me. Her favourite season is, after all, winter. (She shares this controversial opinion with her dad.)