On the one hand, I can scarcely believe it has already been over a month since my last blog post. On the other, I can definitely believe it, considering what an incredibly stressful month it has been.

Perhaps you thought I had abandoned my blog, dear reader, not even a year into this lovely regular posting schedule. I mean, my apparent disappearance suggested as much, so why wouldn’t you? Also, you need not look farther than to 2017 to see that I used to post here very irregularly.

The actual truth is as simple as it is boring: I have been unbelievably busy all February! As a freelancer, I know better than to complain too much about having work. At the same time, I am sure every freelancer would agree that having it spaced out a bit more evenly is better than cramming as much as possible into a short time frame. Putting a huge chunk of cheese on one edge of a slice of bread is not nearly as pleasant as an even distribution of cheese across the whole slice.

So, what have I been up to?

Much of the first half February was spent wrapping up this school year’s series of eight seminars on Western Music History at the Kapellsberg Music School in Härnösand. I started out the series in the music of today, the early part of the 21st century, and walked backwards like an archeologist peeling away at the various layers of music history all the way back to the Middle Ages and the earliest records of written music in the Western world.

If I would’ve had even more time, both time with the class and time to prepare, I would have loved to go both into even more detail on the music of the Middle Ages as well as at least discuss ancient music with the class. As it stands, I barely had time to cover Renaissance music properly. Eight two-hour seminars and a massive 204 000-something character (sic!) Word document later, after the last seminar I felt like I imagine one feels after finishing a marathon. (Drained, but happy, is what I imagine.)

At least, based on the feedback I got from the students, it seems like I succeeded in my primary goal: to articulate and help the students connect the various periods in Western music history together and view them as pieces of a larger puzzle rather than separate lists of names, works, dates and locations. It is quite easy for us smartphone-endowed middle-class folks to quickly look up such tidbits of information, but not nearly as simple or quick to find a broad but still sufficiently substantial overview of the past 1000-plus years of Western musical development.

Berwaldhallen also beckoned a few times in February. The most exciting and rewarding experience was undoubtedly getting to work with a concert featuring the wonderful American pianist Jonathan Biss. Together with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, he played Beethoven’s third piano concerto as well as the companion piece he commissioned to go with it: Caroline Shaw‘s Watermark for piano and orchestra.

In 2015, Biss launched a multi-year commissioning project in partnership with the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, resulting in five new compositions by five different contemporary composers, each responding to one of Beethoven’s five (finished) piano concertos. In naming her piece of this puzzle, Caroline Shaw described it as a symbol of “the memory of an older piece within something new”, that her piece carries “the watermark of Beethoven”.

While I do naturally recognize the importance of Beethoven and many of his works, at the same time I can’t help but feel like his music belongs to that canon of works that are played dutifully at least as often they are played with inspiration. Well, Biss definitely belonged to the latter category. In fact, without exaggeration, in my personal opinion, hearing Beethoven played as well and with such depth of understanding and character rekindled my respect for the piece itself.

Another rewarding and exciting aspect of working with this particular concert was getting to watch Biss work with the orchestra together with its leader, the every bit as amazing violinist Malin Broman. Watching Biss explain and demonstrate his ideas about the Beethoven and Shaw pieces to the orchestra with boyish enthusiasm and the particular kind of self-assured humility that inspires confidence and admiration was fantastic. I already knew, of course, what a brilliant leader Broman can be, so that was no surprise.

If you catch this blog post after Berwaldhallen’s recording has been taken down, or simply want an opportunity to study different interpretations, both good, of the same pieces (which is quite interesting in its own right!), the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra also have a concert recording of the same Beethoven+Shaw coupling available on their website, recorded back in March 2019.

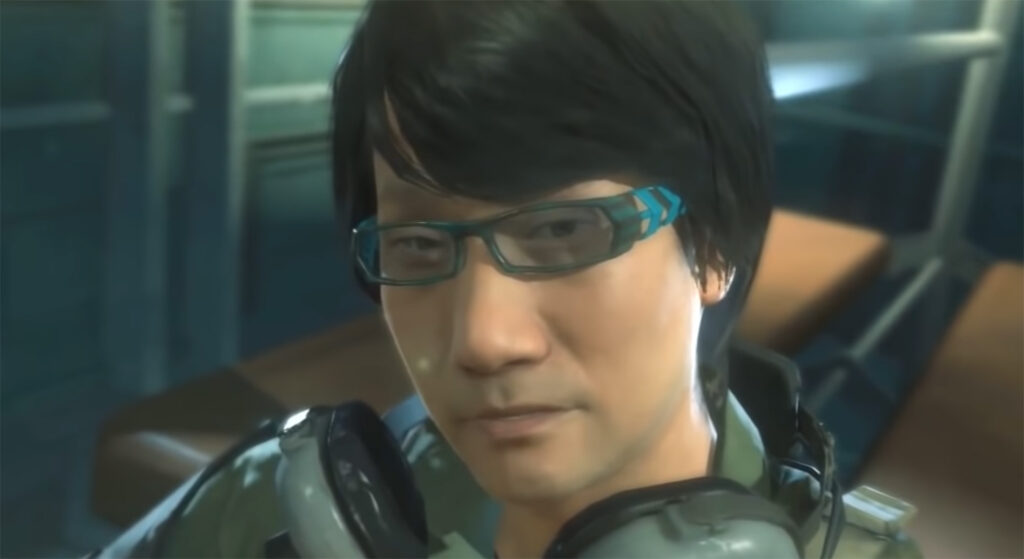

Also in February, I held this school year’s penultimate computer and video game music seminar at the Framnäs Folk High School outside Piteå. As opposed to my Western Music History seminars, I started these back in the 1940s with the very first interactive electronic game device (that we know of). At this point, the fourth session out of five, we had reached the 1990s and the 16- and 32-bit console generations as well as the compact disc taking over and disrupting everything.

By that I mean that in the early years of the compact disc and digital audio dominating computer and video games, the established systems for adaptive, dynamic game music had to be scrapped as they were essentially based on General MIDI with sample-based playback. Perhaps the best-known of these MIDI-based systems is LucasArts’ iMUSE engine, used for the first time in Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge to great effect.

Arguably one of the better composers working with video games today is Wilbert Roget, II who is an undeservedly unsung hero among today’s game composers in my opinion. In the video interview embedded above, game producer and journalist Audun Sorlie talks with Roget about his career as a composer so far. At 28:57, Roget starts talking about his work producing the music arrangements for the remastered version of Monkey Island 2 and describing the difficulty in adapting the iMUSE adaptive system from MIDI to digital audio.

The late 1990s and early 2000s is also when game engines such as id Tech and Unreal arrived, as well as dedicated audio engines such as Wwise and Fmod were initially launched. For well over a decade, adaptive music has been a staple of computer and video games with different games using dynamically changeable music in different ways.

I really enjoy getting to teach both “traditional” music history as well as game music history. Both are quite interesting and exciting in their own right, the latter especially because by really looking at how music has changed throughout the centuries gives you the chance to form a nuanced perspective on today’s music and, as a musician and composer, a way to really formulate what kind of a role you want to play in the contemporary music scene.

Even more things have happened in february, if you can believe it, but I will save those for next week. Yes, I will be back with a new post next week, as usual. Back to our regularly scheduled programming, as they say. I will leave you with a handful of photos of pathologically fearless reindeer and their fuzzy white butts that I passed (at around 4 km/h) on my way up to Piteå last month.